Oil palm production could be a game-changer for Sri Lanka’s rural economy

In April 2021, the Sri Lankan Government took an unprecedented decision of banning palm oil imports and ordered the uprooting of oil palm trees to be replaced with rubber trees. The main reason cited was palm oil’s negative social and environmental impacts based on a contestable report prepared in 2018. After a few days of the order, the import of palm oil that costs Sri Lankan exchequer $ 88 million was reversed. However, the ban on oil palm cultivation continues. The policy of reversing palm oil imports was a prudent one that helped to manage the immediate crisis faced by the local food and confectionary industry. However, what is unintelligible is the decision of the Sri Lankan Government to persist with the ban on oil palm production. The decision becomes even more perplexing considering the rapid dwindling of foreign reserves of Sri Lanka with many import substitution strategies in place today. The situation is so grave that oil import dues owed to Iran to the tune of $ 251 million will be repaid by bartering tea produced in Sri Lanka. If the Sri Lankan tea producers could stand with the Government during a difficult time and help to save foreign exchange and repay its debt, given a chance, the oil palm producers could similarly earn back the foreign exchange in a few years.

But first, let us get the myths and truths of oil palm sustainability out of the way. Emotions have strongly dominated the debate on palm oil. Radical criticism from activist NGOs does not back their positions with transparent scientific research data. Such one-dimensional campaigns motivate consumer opinion, influence policymaking, and pressure the relationships between producing and consuming countries. Unfortunately, like elsewhere in the world, the palm oil sector in Sri Lanka is a victim of a concerted campaign by different anti-palm oil lobbies and radical activists.

As a sustainability student for over two decades across different agricultural commodities, I have come to recognise that there is hardly any inherently sustainable crop. At the same time, almost all crops could be produced in an environmentally and socially sustainable way. In Sri Lanka, oil palm does not replace forest but other plantation crops, primarily rubber or coconut. Therefore, its biodiversity performance needs to be compared with these crops. As found in different studies, the differences in biodiversity between oil palm, rubber, tea, and coconut plantations were neither significant nor conclusive. Cultivation of oil palm can easily provide five times as much vegetable oil per hectare compared to the alternative crops and, in doing so, spare land from being cleared for agriculture. Palm oil sequesters more carbon per hectares than tea and coconut but less than rubber.

Now, what about fertiliser use and water use by palm oil? As per several scientific studies conducted by Sri Lankan scientists, per litre of palm oil requires lesser fertiliser and less water than coconut, dry rubber or tea. It is cultivated in areas with 2,500 mm rainfall, which exceeds its water needs of ca 1,300 mm. Moreover, palm oil mainly uses rainwater almost everywhere globally, and there is no evidence of palm oil plantations leading to groundwater depletion.

So, can palm oil emerge as a strategic commodity for Sri Lanka? The edible oil consumption over the last decade has been growing at a CAGR of 3%. At present, local consumption is around 264,000 MT, from which only about 20-25% is produced locally. Expanding in coconut from the present 40,000 MT to meet the shortfall is neither economically viable nor technically feasible. Presently, Sri Lankan oil palm cultivation covers approximately 12,000 Ha, less than 1% of the total agricultural land in the country. In 2021, the country paid an average of Rs. 475 per kg for imported crude palm oil. The same imported crude palm oil in India costs Rs. 300 per kg. The massive taxes (55% of the total CPO price) imposed on imported palm oil in Sri Lanka to balance it with coconut oil prices will only make sense if backed up by a comprehensive plan for expanding local oil palm cultivation.

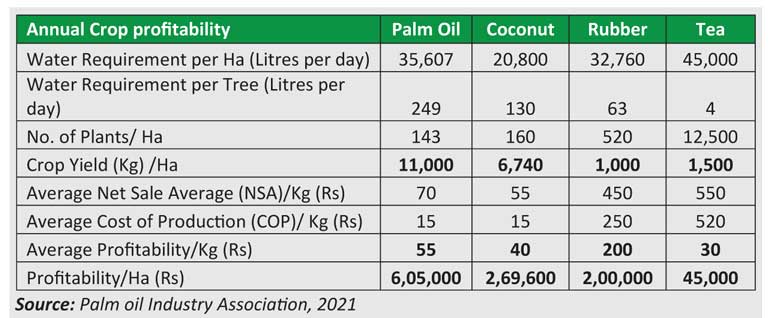

In Indonesia and Malaysia, numerous studies showed that oil palm cultivation contributes to income gains, capital accumulation, and higher expenditures on food, health, education, and durable consumer goods in smallholder farm households (Alwarritzi et al. 2016). A study in Ghana showed that oil palm farmers have higher incomes and suffer less from multidimensional poverty than other farmers (Ahmed et al. 2019). So, can palm oil play a similar role in Sri Lanka? From the table, we could see that the profitability from palm oil per hectare would be Rs. 605,000 compared to Rs. 269,600 for coconut, Rs. 2,000 for rubber or Rs. 45,000 for tea. It means that while using much lesser land and almost the same water level, oil palm can provide a much better financial return to a farmer.

The benefits of oil palm production are not restricted to farm households alone, but it also benefits the community. Oil palm is relatively labour intensive because most operations are carried out manually. In Indonesia, oil palm on large company plantations and smallholder farms created rural employment and economic benefits for many landless labourers. In Ghana, those employed in oil palm are better off than those employed in other agricultural subsectors. Many young adults migrate to oil palm regions in Uganda because of lucrative new employment opportunities. In Sri Lanka, as per the Household Income & Expenditure survey (2016), oil palm workers received around Rs. 40,000 additional income (annually) compared to a rubber worker household, and Rs. 75,000 additional income compared to a tea worker household. Palm oil stands out as a crop with higher income attributes to plantation workers.

Currently, the Sri Lankan palm oil sector has only minor smallholder participation. Only a few non-RPC (Regional Plantation Companies) entities are presently operational in oil palm plantations and established in the same regions where major RPCs operate. So, how can Sri Lanka create an oil-palm ecosystem where smallholders and large plantations could co-exist? Three critical things would be needed for such a transition to happen.

Firstly, the ban on oil palm production needs to be revoked. Such a ban creates foreign exchange losses for Sri Lanka while the massive taxes paid by the palm oil importing companies are passed on to the Sri Lankan consumers. The Sri Lankan farmers should not be denied benefitting from the most profitable plantation crop on earth and allow Sri Lankan consumers to buy reasonably priced, locally produced sustainable palm oil.

Secondly, the Government may consider setting up a palm oil mission with a vision of producing 300,000 MT of palm oil in the country. A special-purpose fund could be created partly covered by the Government and partially funded by international banks like the Asian Development Bank that will support the development of high yielding seeds and support the setting up of the Sri Lankan Palm Oil Board that will produce a palm oil national plan and regulate oil palm production and trade in the country.

Thirdly, Sri Lanka may devise its sustainability framework for producing oil palm. The world’s biggest producers like Indonesia and Malaysia, have decided to create their national sustainability frameworks called Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) and Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO), respectively. India has developed its national sustainability framework in the form of the Indian Palm Oil Sustainability (IPOS) framework. Most oil palm producers are certified by external auditors against those standards, assuring that the oil palm is produced in a socially and environmentally sustainable way. Sri Lanka may also choose to certify its oil palm producers under one of the voluntary certification standards like Round Table on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), Rainforest Alliance or Fair Trade.

Nation-building and achieving the desired economic growth are two issues Sri Lanka has aimed to achieve for a long time. Towards that direction, it has prioritised achieving United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The core of sustainable development is built around a strategy that aims to balance the different and competing needs of a nation’s environment, society, and economy. Oil palm contributes to 15 goals/sub-goals out of 17 SDGs. If the Government, industry and NGOs join hands to give palm oil a chance in Sri Lanka, it can create an even bigger socio-economic impact than tea, coconut or rubber sub-sectors.

Oil palm nursery in Sri Lanka

Oil palm plantation in south Sri Lanka